Page 39 - Igor Ž. Žagar in Ana Mlekuž, ur. Raziskovanje v vzgoji in izobraževanju: mednarodni vidiki vzgoje in izobraževanja. Ljubljana: Pedagoški inštitut, 2020. Digitalna knjižnica, Dissertationes 38

P. 39

inequality, poverty and education in the post-yugoslav space

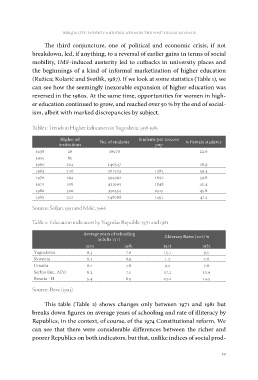

The third conjuncture, one of political and economic crisis, if not

breakdown, led, if anything, to a reversal of earlier gains in terms of social

mobility, IMF-induced austerity led to cutbacks in university places and

the beginnings of a kind of informal marketization of higher education

(Ružica; Kolarić and Svetlik, 1987). If we look at some statistics (Table 1), we

can see how the seemingly inexorable expansion of higher education was

reversed in the 1980s. At the same time, opportunities for women in high-

er education continued to grow, and reached over 50 % by the end of social-

ism, albeit with marked discrepancies by subject.

Table 1: Trends in Higher Education in Yugoslavia, 1938-1985

Higher ed No. of students Students per 100,000 % Female students

institutions pop 22.6

16978

1938 26 1282 28.9

1955 81 140547 1850 39.4

1960 204 261203 1848 39.8

1965 246 394992 1515 45.4

1970 294 411995 1491 45.8

1975 356 350334 47.4

1980 300 348068

1985 322

Source: Šoljan, 1991 and Milić, 1966

Table 2: Education indicators by Yugoslav Republic 1971 and 1981

Average years of schooling Illiteracy Rates (10+) %

(adults 15+)

1971 1981 1971 1981

15.1 9.5

Yugoslavia 6.3 7.6 1.2 0.8

Slovenia 9.0 5.6

Croatia 8.2 8.9 17.2 10.9

Serbia (inc. APs) 23.2 14.5

Bosnia - H 6.7 7.8

6.2 7.5

5.4 6.9

Source: Bevc (1993)

This table (Table 2) shows changes only between 1971 and 1981 but

breaks down figures on average years of schooling and rate of illiteracy by

Republics, in the context, of course, of the 1974 Constitutional reform. We

can see that there were considerable differences between the richer and

poorer Republics on both indicators, but that, unlike indices of social prod-

39

The third conjuncture, one of political and economic crisis, if not

breakdown, led, if anything, to a reversal of earlier gains in terms of social

mobility, IMF-induced austerity led to cutbacks in university places and

the beginnings of a kind of informal marketization of higher education

(Ružica; Kolarić and Svetlik, 1987). If we look at some statistics (Table 1), we

can see how the seemingly inexorable expansion of higher education was

reversed in the 1980s. At the same time, opportunities for women in high-

er education continued to grow, and reached over 50 % by the end of social-

ism, albeit with marked discrepancies by subject.

Table 1: Trends in Higher Education in Yugoslavia, 1938-1985

Higher ed No. of students Students per 100,000 % Female students

institutions pop 22.6

16978

1938 26 1282 28.9

1955 81 140547 1850 39.4

1960 204 261203 1848 39.8

1965 246 394992 1515 45.4

1970 294 411995 1491 45.8

1975 356 350334 47.4

1980 300 348068

1985 322

Source: Šoljan, 1991 and Milić, 1966

Table 2: Education indicators by Yugoslav Republic 1971 and 1981

Average years of schooling Illiteracy Rates (10+) %

(adults 15+)

1971 1981 1971 1981

15.1 9.5

Yugoslavia 6.3 7.6 1.2 0.8

Slovenia 9.0 5.6

Croatia 8.2 8.9 17.2 10.9

Serbia (inc. APs) 23.2 14.5

Bosnia - H 6.7 7.8

6.2 7.5

5.4 6.9

Source: Bevc (1993)

This table (Table 2) shows changes only between 1971 and 1981 but

breaks down figures on average years of schooling and rate of illiteracy by

Republics, in the context, of course, of the 1974 Constitutional reform. We

can see that there were considerable differences between the richer and

poorer Republics on both indicators, but that, unlike indices of social prod-

39